How To Easily Understand Callbacks In JavaScript

I come from a Java background. When I was first learning Node.JS and JavaScript, I had what I thought was a decent level of understanding in JavaScript and ran into a problem similar to this while I was trying to do something involving pulling data from a database, storing it in a variable and then doing something with that data.

var songsList = myDatabaseObject.getSongsList();

console.log(songsList); // undefined, why?Seems like something pretty elementary right? Get data from database, store it in a variable and then print it- right? Well, JavaScript isn’t procedural in the way that Java or C++ is. Simply put, we can’t expect that our code will go ‘line by line’ in JavaScript because JavaScript is another type of beast.

Lets say we were to write a class for a Person. This person wakes up and goes through their morning routine every morning- one step at a time in order. We might represent it this way in Java:

public class Person {

// Constructor

public Person() {

}

public void wakeUp() {

// do wakeup stuff

}

public void putOnPants() {

// do the putting on of pants

}

public void putOnShirt() {

// do the putting on of a shirt

}

public void putOnShoes() {

// put those shoes on, boi

}

public void goToSchool() {

// now go to school!

}

public static void main(String [] args){

Person person = new Person();

person.wakeUp(); // 1st we do this

person.putOnPants(); // then this

person.putOnShirt(); // then this

person.putOnShoes(); // then this

person.goToSchool(); // and finally this

}

}And perhaps in JavaScript we would likely do something like this:

// Constructor

function Person() {

}

Person.prototype.wakeup = function(callback){

// do wakeup stuff

callback();

}

Person.prototype.putOnPants = function(callback){

// do the putting on of pants

callback();

}

Person.prototype.putOnShirt = function(callback){

// do the putting on of a shirt

callback();

}

Person.prototype.putOnShoes = function(callback){

// put those shoes on, boi

callback();

}

Person.prototype.goToSchool = function(callback){

// now go to school!

}

var person = new Person();

person.wakeup(function() {

person.putOnPants(function() {

person.putOnShirt(function() {

person.putOnShoes(function() {

person.goToSchool();

});

});

});

});Now, I know what you’re thinking. “That last block of code looks disgusting.” Hey, trust me- when I first started, I was guilty of doing stuff like this all the time. In the JS world, we call this “Callback Hell”. If it doesn’t quite make sense how this works, we’ll get into that in a second.

The reason we need to use callbacks in JavaScript is because of the concept of asynchronicity and JavaScript’s non-blocking behavior.

Synchronous behavior is what we are used to! The Java example supports this. For example, if you were to wake up in the morning, you would first wake up, then put on your pants, then put on your shirt, then put on your shoes and then go to school! The code executes in order in the Java code, line-by-line. Even though the method named ‘putOnPants()‘ might be 20 lines of code containing the procedure of the person deciding which pair of pants to put on, we know for sure that we can’t get to goToSchool() without first putting on your shirt and then putting on your shoes. This is because Java blocks the next method call until the current one is finished.

However, JavaScript doesnt block method calls. So if we did the same thing in JavaScript…

person.wakeUp(); // we want to do this first

person.putOnPants(); // and then this

person.putOnShirt(); // then this

person.putOnShoes(); // then this

person.goToSchool(); // and finally this…we would probably notice that we executed person.goToSchool() even before all the other methods were finished executing. So theoretically, you could be on your way to school without a pair of pants, shirt or shoes on! Yikes.

We deal with a lot of asynchronous behaviour in JavaScript. Here are a few examples:

- my original problem: I want to get some data from the database and then print it out.

- we want to ask for some data from a server and then do something with the response

- a user clicks on a button and we want to do something after they click on it.

The common theme here among each of these?

They can happen at any point in time (asynchronous). So we need some sort of mechanism for ‘handling an event’, so to speak; ie: we need some way to do one thing after the next.

This is why we use callbacks. In JavaScript, functions can be passed as first-class objects which is a fancy way to say that “they can be passed as regular variables” and these functions don’t always need to be declared ahead of time.

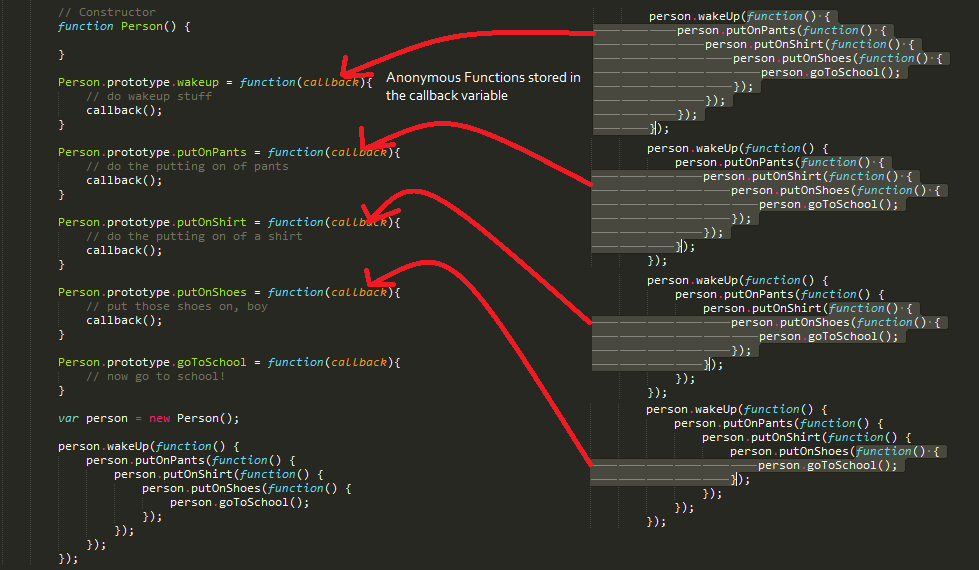

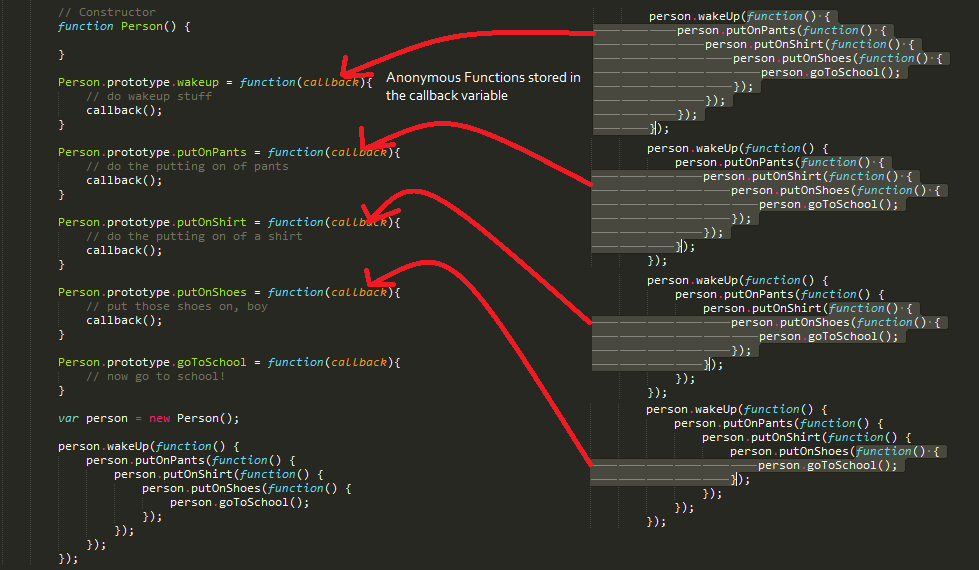

If you take a look at the example below, hopefully this simplifies what’s actually happening.

- Inside of the person.wakeUp() arguments we pass in an anonymous (unnamed) function.

- In the actual method, this function is stored in the callback variable in the parameters.

- After we do wakeup things, we invoke that callback function which is storing the anonymous function that we passed in.

- Inside of the first anonymous function, we make a call to person.putOnPants() and pass in another anonymous function.

Anonymous functions being executed inside of nested method calls on the Person class.

.. and the process repeats until we get to the last anonymous function which simply calls person.goToSchool(). We don’t bother to pass in an argument but if you wanted to do something after the goToSchool() method, you’d just have to do what we did here before. Pass in a function in the arguments and invoke that function at the end of goToSchool() through the callback when you’re done doing all the stuff in goToSchool().

So what about my original problem, how can I fix it?

// lets say that the function for myDatabaseObject.getSongsList looked like:

Database.prototype.getSongsList = function(callback) {

var db_connection = MySQL.getConn();

var sql = "SELECT SONG_TITLE FROM LIBRARY";

db_connection.executeStatement(sql, function(results, err){

if(!err) {

callback(results); // notice that we can pass in arguments to callback since it's of type [function]!!

}

})

}

// and then we did

var songsList = myDatabaseObject.getSongsList(function(result){

console.log(result); // ['Hit Me Baby One More Time', 'Never Gonna Give You Up']

});There! That works, that doesn’t look to bad either- the result is clean and simple. However, for our problem with many nested callbacks, that didn’t look good at all. In fact, most would say it’s bad practice to have callbacks nested that deep. Here’s another solution to that problem without using callbacks.

// Constructor

function Person() {

}

Person.prototype.initMorningRoutine = function(){

console.log("Better get up and get ready");

this.wakeup();

}

Person.prototype.wakeup = function(){

// do wakeup stuff

console.log("Alright, I'm up. Let's put on some pants.");

this.putOnPants();

}

Person.prototype.putOnPants = function(){

// put on pants

console.log("Pants- check. Now what shirt should I wear?");

this.putOnShirt();

}

Person.prototype.putOnShirt = function(){

// do the putting on of a shirt

console.log("Wearing my fav band tee, it's going to be a good day. Now the shoes.");

this.putOnShoes();

}

Person.prototype.putOnShoes = function(){

// put those shoes on, boy

console.log("Docs are on, ready for school.");

this.goToSchool();

}

Person.prototype.goToSchool = function(){

console.log("Bye mom! I'm leaving for school now!");

// now go to school!

}

var person = new Person();

person.initMorningRoutine();Now if you ran this in the console, here’s what you would see!

Better get up and get ready

Alright, I'm up. Let's put on some pants.

Pants- check. Now what shirt should I wear?

Wearing my fav band tee, it's going to be a good day. Now the shoes.

Docs are on, ready for school.

Bye mom! I'm leaving for school now!Now, you're ready to dive deep into JavaScript and the next time you encounter a callback, it'll be a breeze for you.

Stay in touch!

Join 20000+ value-creating Software Essentialists getting actionable advice on how to master what matters each week. 🖖

View more in Web Development